David & Goliath is Not About Slaying Your Giants (and that’s good news)

House of David premiered on Amazon Prime in February of 2025. Within its first seventeen days on the streaming platform, the series had drawn twenty-two million viewers and earned a second season. By the time the season drew to its dramatic close, over forty-four million people worldwide had tuned in. Amazon’s gamble became a blockbuster hit.

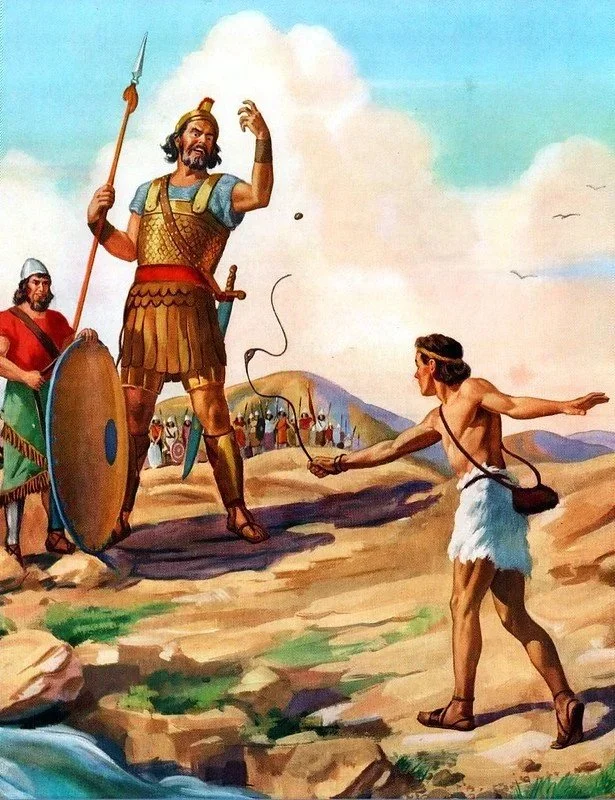

The show’s climax, of course, was the epic battle scene between young David and the mighty Goliath—a Philistine warrior standing somewhere between seven and nine feet tall. Those two episodes propelled the series to the number one slot on Prime Video’s streaming charts.

Predictably (and admirably), pastors everywhere capitalized on the cultural moment and turned their congregations to the Scriptures. The David and Goliath faceoff takes place in 1 Samuel 17. The typical “David and Goliath” sermon goes something like this:

· Goliath mocked Israel, God’s chosen nation.

· The king on the throne was too afraid to fight Goliath.

· Because David had faith in the LORD, he slew the giant.

· If you have faith in the LORD, you can slay your giants, too.

· Be like David.

Is this the way the biblical author imagined his audience would understand the story, or could there be more to unearth?

In a sermon titled “David’s Courage,” Tim Keller challenges what he calls a shallow “face your fears” reading of the story.[1] Elsewhere, he reminds us that we must “get to Jesus every week.”[2] I agree. The entire Old Testament moves us toward the cross of Christ. But before we look forward to the crucifixion, let’s first look back to the garden.

Serpent Imagery in the Story

Every biblical author assumed one thing of their readers (or, more likely, hearers): That they had a robust Old Testament vocabulary. In other words, they heard echoes of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy in the stories of Joshua, the Judges, the Kings, the Psalms, and the Prophets. The story of David and Goliath teems with references to Genesis 3.

Take, for instance, Goliath’s battle gear. One scholar says, “The portrayal of Goliath may well be ‘the most detailed physical description of any found in scripture.’”[3] Most notable, according to B. A. Verrett and J. S. DeRouchie, is the amount of ink spilled on his “coat of mail” (1 Sam. 17: 5), made up of five thousand shekels (about 125 pounds) of bronze. The bronze was fashioned into plates resembling the scales of a serpent, providing both maximum protection and mobility.

The author wants us to remember another scene between God’s people (Adam and Eve) and a serpent. In fact, the great tension of the story of Scripture is that someday, an offspring of the woman will rise up and bruise the serpent’s head, who will, in turn, injure his heel (Gen. 3:15). David partially fulfills that prophecy and provides a signpost pointing forward. Verrett states,

When Goliath fell facedown, this may allude to the serpent eating the dust of the earth (Genesis 3:14)…Not only did David cause Goliath to fall down, but he also decapitated Goliath. David killed Goliath not with the stone but by removing his head (1 Samuel 17:46, 51; ראשׁ). Leithart captures the significance of this: “Goliath was dressed like a serpent with his scale armor, and he died like a serpent, with a head wound, just as the Philistine god Dagon had his head crushed.”[4]

Rather than seeing an exhortation to “slay their giants,” Jews would’ve found comfort in YAHWEH’s deliverance exacted through David and anticipated another anointed king—one who would fight on Israel’s behalf and reign on earth forever.

David’s victory, then, was never meant to terminate on David himself. It was meant to shape Israel’s hope—training them to look for a deliverer who would fight for them, not demand that they fight like him. And that expectation becomes even clearer when we consider not just what the story tells us, but how stories work on us as hearers.

The Cross-shaped View

With all the many different ways to convey information, why did Jesus teach through stories (aka parables)? One scholar says, “Good stories do more than create a sense of connection. They build familiarity and trust, and allow the listener to enter the story where they are, making them more open to learning.”[5]

Did you catch that? The goal of a story is for the hearer to place themselves in the drama. Preachers do well to encourage the practice. Problems in biblical interpretation arise when we place ourselves in the hero’s role.

We do it all the time. Most of us hear the story of the Good Samaritan and fancy ourselves the one who would sling the half-dead traveler over our donkey and pay the innkeeper to nurse him back to health. We fail to realize that, as Martin Luther preached, we are not the rescuer in the story at all but the half-dead sojourner, helpless to save ourselves.[6]

The story of Jesus is the story of David and Goliath. Not moral instruction, but gospel proclamation—good news for those who cannot save themselves. We are not David, and our trials are not our giants. We are Israel, helpless before an enemy (the flesh, the world, and the devil), in desperate need of a savior.

We cannot help ourselves.

We cannot pull ourselves up by our bootstraps.

We cannot dig deeper or try harder.

We need a conqueror who can stare down death and rise triumphant. Jesus is the true and better David, who dealt Satan a death blow on the cross, and will finish him off once and for all when he returns.

And he will return.

A Better Story

The good news of David and Goliath is not that we can slay our giants. Not when the giant is sin and death.

The good news is that, in our helplessness, while we were yet sinners, Christ took our sins upon himself, died in our place, and rose again from the grave.

The serpent has suffered the death blow. Yes, in his thrashing, he still causes unimaginable damage. But his days are numbered and his time is short.

As far as your “little-g-giants” are concerned, you may or may not beat the diagnosis.

You may or may not overcome your obstacles.

You may or may not get the promotion.

Or the family you long for.

Or the life you dreamed of.

God does not promise us those things in this world. Instead, he provides the power and comfort of the Holy Spirit. In Christ, you have access to God the Father who hears your prayers and works all things together for the good of those who love him and are called according to his purpose. And you have the guarantee of the resurrection and life in the world to come.

Where you will rejoice eternally in the presence of Jesus.

And that’s a better story, by far.

[1] Timothy Keller, “David’s Courage” (Redeemer Presbyterian Church / Gospel in Life sermon, May 3, 2015).

[2] Timonth Keller, “Moralism vs. Christ-Centered Exposition,” accessed on December 21, 2025, https://www.monergism.com/thethreshold/articles/onsite/moralismkeller.

[3] Ronald F. Youngblood, “1, 2 Samuel,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: 1 Samuel–2 Kings (Revised Edition), ed. Tremper Longman III and David E. Garland, vol. 3 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009), 178.

Youngblood quotes Boogaart, p. 207.

[4] Brian A. Verrett, The Serpent in Samuel: A Messianic Motif, Resource Publications, 2020, 157. Accessed on on December 22, 2025, https://intertextual.bible/text/genesis-3.14-1-samuel-17.49?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[5] Vanessa Boris, “What Makes Storytelling So Effective for Learning?” in Harvard Business Impact, 2025, accessed on December 22, 2025, https://www.harvardbusiness.org/insight/what-makes-storytelling-so-effective-for-learning/#:~:text=Storytelling%20can%20be%20effective%20for%20learning%20because,than%20learning%20derived%20from%20facts%20and%20figures.

[6] Martin Luther, 1534 House Postil on the Parable of the Good Samaritan.